Segregation, a defining, disruptive force in American history, didn’t just create obstacles for Black Americans—it cultivated resilience within Black communities and ignited the legacies of prestigious Black American-led organizations and institutions. A notable example, the National Bar Association (NBA), was founded in the pursuit of equity in the legal profession and stands as the oldest and largest network of African-American lawyers and judges in the United States.

Reconstruction (1865-1877), an era that sought to empower Black Americans with protections and new opportunities in a post-slavery society, led to the rise of “separate but equal” statutes that extended into the era of Jim Crow. “Jim Crow” is a term for a collection of laws and ordinances passed at the state and local levels between 1877 and the mid-20th century that mandated segregation by race in public facilities. Likewise, organizations like the American Bar Association (ABA)s— and most local and state bar associations— did not permit Black lawyers to join their organizations.

In the early 20th century, Greenville, Mississippi, and similar southern cities were hubs for Black lawyers and civil rights advocacy. The regions were catalysts for action, enabling Black legal professionals to unite for mutual advancement and civil rights advocacy. This organizational need would be underscored in 1924, when five of the twelve founding members of the forthcoming Negro Bar Association were denied entry to the Iowa State Bar.

In 1925, in Des Moines, Iowa, the Iowa Colored Bar Association organized a national convention of Black lawyers. The convention summoned Black lawyers from across the nation, all of whom shared experiences of exclusion, unequal access, and racial barriers to practicing and studying law. The result of the convention led to the founding and incorporation of the Negro Bar Association.

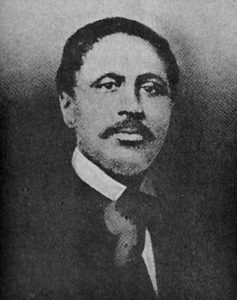

On August 1st, 1925, twelve lawyers—George H. Woodson, S. Joe Brown, Gertrude E. Rush, James B. Morris, Charles P. Howard, Sr., Wendell E. Green, C. Francis Stradford, Jesse N. Baker, William H. Haynes, George C. Adams, Charles H. Calloway, and L. Amasa Knox—met in Des Moines, Iowa to officially found the Negro Bar Association (NBA).1 Excluded from the American Bar Association, ABA, these lawyers sought to “advance the science of jurisprudence, uphold the honor of the legal profession, promote social intercourse among the members of the American Bar, and protect the civil and political rights of all citizens of the several states and the United States.”1

Throughout the early 20th century, The Negro Bar Association served as the legal backbone for the civil rights movement while simultaneously fighting for equity in the legal profession. In the 1930s, members of the Negro Bar Association were challenged with exclusion from municipal and private law libraries. However, Black lawyers achieved success in the case of Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (1938).

In 1938, aspiring lawyer Lloyd Lionel Gaines was denied admission to the University of Missouri School of Law due to his race. Gaines sued the institution for discrimination. The Missouri Supreme Court upheld the state’s argument that it could pay for Gaines to attend law school out of state, rather than integrate, reinforcing “separate but equal” policy.

However, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed that ruling, declaring that Missouri could not satisfy the constitutional requirement of equal protection when sending Gaines elsewhere. If the state provided legal education which included protection for white students, it had to offer substantially equal facilities to Black students within the state. Before the case could go further, Gaines was reported missing on March 19th, 1939. His disappearance remains an unsolved mystery.

Gaines’ case challenged the broader legal principles of segregation in education. Sweatt v. Painter (1950) further emphasized that segregated law schools were inherently unequal—particularly due to lack of access to law libraries, alumni networks, and faculty resources. These victories chipped away at the precedent set by Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which upheld segregation under the “separate but equal” doctrine.

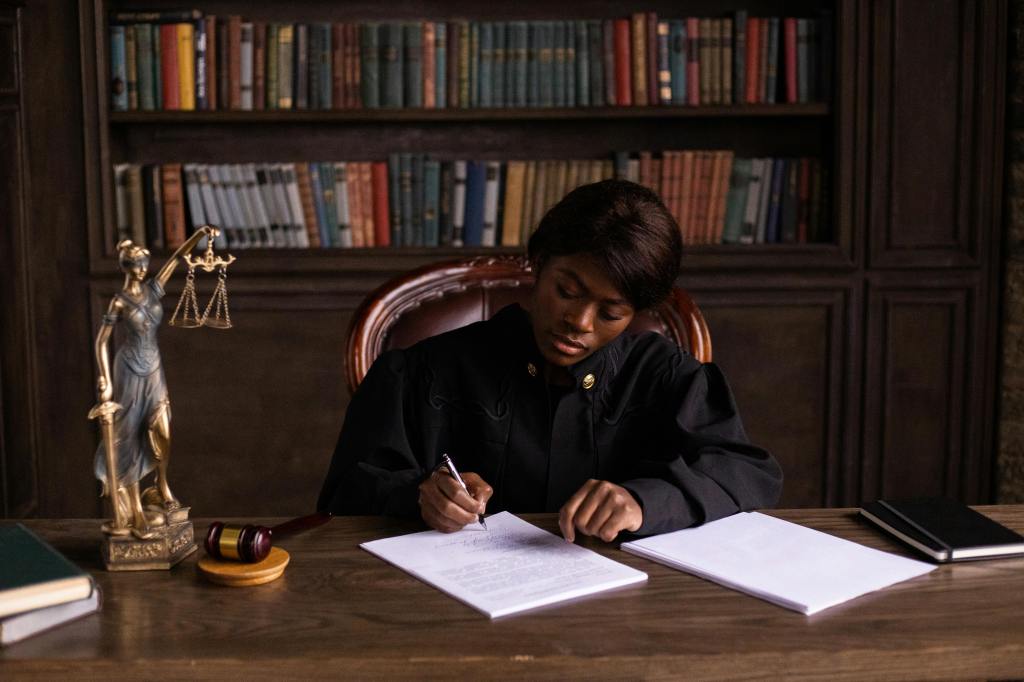

Since incorporation, the Negro Bar Association’s name was later renamed the “National Bar Association.” Today, exactly 100 years later, we celebrate the founding and legacy of the nation’s oldest and largest national association of African-American lawyers, judges, law professors, and students. With a network of over 67,000, the NBA has over 80 chapters throughout the United States and affiliations with lawyer organizations in Canada, the United Kingdom, Africa, Morocco, and the Caribbean.

Should you find yourself interested in National Bar Association’s causes, you can view and attend their upcoming events at https://nationalbar.org/events/.

Leave a comment